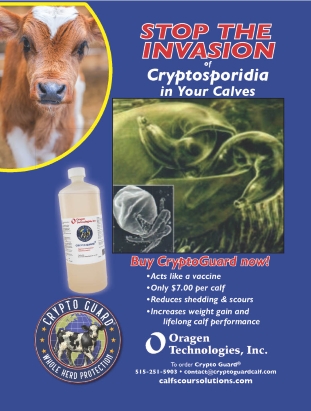

Cryptosporidiosis in Calves

Cryptosporidiosis in Calves

Cryptosporidiosis is a protozoal disease, similar to coccidiosis in several ways. Protozoa are one-celled animals and most kinds are harmless. But several types cause disease in animals and most of these are transmitted by the fecal-oral route; the protozoa are passed in the feces of an infected animal and ingested by a susceptible animal via contaminated feed or water or when licking a dirty hair coat or suckling a dirty udder.

The protozoa that cause cryptosporidiosis are found almost everywhere. Various types infect humans, sheep, goats, deer, squirrels, etc. but only one type infects cattle. This same type can also infect humans. Another strain affects only humans. Several strains affect humans and various other animals but not cattle. Wildlife such as raccoons occasionally pass crypto to livestock.

Where the Protozoa Thrives

These protozoa survive in moist conditions and can live for about 170 days in streams of water. They can also live in mud or wet, contaminated ground, but drying or freezing will eventually kill them. After being ingested, they multiply in the calf’s intestine, causing diarrhea. It’s rare to find this pathogen in calves older than 4 months or in adults, but many calves are infected during their first months of life.

In earlier years, this disease was a problem only in dairy cattle and was estimated to affect up to 70% of dairy calves 1 to 3 weeks of age, with rate of infection on some farms as high as 100%. Now, however, this disease has appeared in beef herds as well. Though crypto is often mild and self-limiting (runs its course without treatment and the animal recovers), it can be life threatening in any human or young animal with a compromised immune system or concurrent illness with some other disease. In one study, 5% of cows tested were carriers, spreading a few protozoa continually in feces. Thus these organisms are fairly common in the environment and in the water on certain farms.

What Can We do?

Geof Smith, DVM, North Carolina State University, says this intestinal infection is hard to prevent or treat because it’s not viral or bacterial. “We’re probably never going to have a good vaccine, because there are almost no vaccines for protozoal diseases,” he says. The best defense against crypto is a healthy herd in good condition, in a clean environment. Herd health can be compromised by improper nutrition, so whenever you are dealing with crypto, take a hard look at the trace mineral status of the animals—especially selenium and copper, since they are crucial to a strong immune system and seem to be especially important in whether or not cattle are susceptible to crypto.

This disease can be deadly if young calves are challenged with several pathogens at once, such as bacterial and/or viral scours along with the protozoa. Calves with severe, hard-to-treat diarrhea usually have mixed infections. Once you’ve had crypto on your farm and the environment is contaminated, it is almost impossible to get rid of it. Thus the best defense is a healthy herd and clean calving area, to keep calves from becoming sick with crypto.

The Disease

The life cycle of cryptosporidia is different from that of coccidiosis. With coccidiosis, calves don’t break with diarrhea until they are at least 3 weeks old. By contrast, a calf with crypto can develop diarrhea as young as 4 days of age if he was born in a contaminated place and ingests a large number of protozoa soon after birth. After an oocyst is ingested, it attaches to the intestinal lining to sporulate and multiply, similar to the multiplication stages of coccidia, but the incubation time for crypto is only 2 to 7 days. Thousands of new oocysts are then passed in the feces of that calf for 3 to 12 days. Infection persists until the calf develops enough immune response to eliminate the parasite from the body.

When protozoa attach to the intestinal lining, white blood cells migrate to the site to fight off the infection, creating intense inflammation. The only way the calf can get rid of the pathogen is to get rid of the cell it’s attached to, so the lining is shed. The raw gut wall can no longer absorb fluid and nutrients, so everything shoots on through, creating watery diarrhea.

Effects of the Disease

Peak diarrhea occurs about 3 to 5 days after the calf ingests oocysts. The gut usually heals in a few days, but without intensive supportive treatment some calves will die from dehydration before the gut heals. Calves younger than 3 weeks of age usually take longer to regenerate the damaged gut lining than an older calf, and the young ones also dehydrate more quickly.

Just like coccidiosis, after a calf gets over the infection he has some resistance. Even if he encounters the crypto protozoa again, he’s less likely to get sick again but may continue to shed a few oocysts. Adult cattle usually don’t become ill with crypto but can serve as a source of infection for calves.

Symptoms

Calves with crypto usually have diarrhea that persists for several days even if you treat them, since protozoa do not respond to antibiotics. The feces are usually watery, pale or greenish in color, but sometimes yellow, cream-colored or gray. The fluid feces do not contain blood because the damage is not that deep (in contrast to the bloody diarrhea of coccidiosis).

You may see mucus or shreds of tissue in the feces. The calf may be dull and not interested in feed or sucking a bottle. He may be dehydrated and/or show signs of gut pain. Persistent diarrhea may result in weight loss and emaciation. If complicated by concurrent infection with bacteria or viruses, the calf is usually much sicker. It may take diligent nursing care and frequent administration of fluids to keep him alive long enough for the gut to heal.

Treatment

“Unlike bacteria, we can’t kill these protozoa with antibiotics. We don’t have any drugs in this country that have been shown to work as an effective treatment for crypto,” says Smith.

There’s no specific medication for crypto. Supportive care (fluids, electrolytes and good nutrition) can often save the calf if started early. If the calf is not nursing, he should be force-fed milk or milk replacer as well as extra fluids, or he may become weak. Studies have shown that Banamine is also helpful, to reduce inflammation and to make the calf less miserable—so he’ll be more apt to keep eating. IV fluids may be necessary for calves that are unable to absorb oral fluids.

David Rethorst, DMV (Beef Health Solutions, Wamego, Kansas) says that in order to save these calves you need to use a good electrolyte solution that’s high in bicarb content, and lots of it. “Give 2 quarts, 3 to 4 times a day,” says Rethorst. The more often, the better. You can’t overdo the fluid/electrolytes for these calves.

Prevention

Make sure you never bring this bug to your farm if you don’t have it already. If this disease is already on your place, keep all calving cows and young calves in a clean environment, so calves won’t be exposed early in life by ingesting protozoa with contaminated feed or water, or nursing a dirty udder if they are allowed to nurse colostrum from the dam before being separated from her. If a pregnant cow lies in dirty bedding or on contaminated ground, she may get feces on her udder and the calf may ingest oocysts with his first nursing. The same precautions should be taken as for preventing spread of coccidiosis.

There is no vaccine that is very effective to prevent crypto, though researchers have worked on this. Control depends on cleanliness, avoidance of stress and crowding, and making sure cattle have clean feeding and bedding areas.

Isolate any calf that develops diarrhea if the calves are being housed in groups or pairs. You don’t want the sick one spreading oocysts and infecting other calves. Make sure YOU don’t transmit the disease to other animals. Change clothes and footwear or rinse your boots in a disinfectant solution, wash your hands, and don’t track feces from the sick pen to other locations.

Make sure every newborn calf gets adequate colostrum soon after birth. Even though cows don’t produce many antibodies against protozoa, they produce some if they’ve been exposed to crypto, and this may give their calves some protection. In trials with crypto, the calves that had adequate colostrum were more difficult to intentionally infect with this disease. Healthy, unstressed calves with high levels of antibodies from colostrum also won’t develop other diseases that might put them at risk for a serious case of cryptosporidiosis.

Be Careful Handling Sick Calves

Cryptosporidiosis can be spread from calves to humans. Calves or humans in good health can usually handle exposure and not become ill. Very young calves or humans, or elderly people, or anyone with a compromised immune system may become seriously ill, however. Crypto can cause devastating illness in vulnerable people or calves, such as calves that did not get colostrum at birth. Be careful when treating sick calves so you don’t inadvertently spread the disease to a vulnerable human. Wash your hands and change your clothes when you come indoors, especially if you have young children or elderly adults in your home.

Hydrogen peroxide is one disinfectant that will kill crypto oocysts. If you are working around calves with diarrhea, make sure you protect yourself (and others) from becoming infected,” says Smith.

Rethorst recommends wearing exam gloves when handling/treating calves with crypto. “Wash your hands afterward. Don’t grab a fresh dip of Copenhagen while you are treating calves!”

He had a client who got crypto from handling sick calves. “That rancher ended up passing it to his 3-month-old son because he didn’t wash his hands and the ‘bug’ got carried into the house. Everyone survived, but it was a challenge getting through it. People need to realize there is human risk with this disease—even more than with an E. coli or Salmonella.

November 2024

By Heather Smith Thomas

Leading Cattle Industry News found Here: Home – American Cattlemen