Frequently Asked Questions on Gastrointestinal Parasites in Goats

Frequently Asked Questions on Gastrointestinal Parasites in Goats

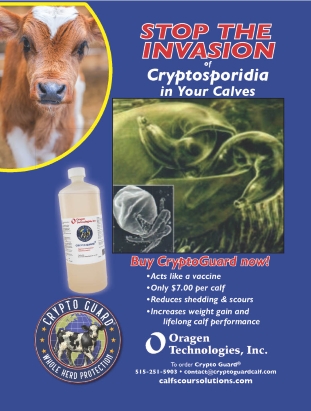

Parasites cause disease when they are present in large numbers or when the host animal is weakened by another disease or by poor nutrition. Damage to the host occurs when the parasites attach to the lining of the gastrointestinal tract and ingest blood – large numbers of parasites can create anemia from blood loss. Damage can also occur from other parasites when they either attach to the lining of the gastrointestinal tract and cause it to become inflamed, or they live in the lumen (open area) of gastrointestinal tract and have access to ingested feed nutrients before the host can digest them. This can result in impaired ability of the host animal to absorb nutrients, causing poor body condition (thinness), poor growth rates, low milk production, and/or poor hair coat or fleece growth. Some parasites cause a reduction in appetite by the host animal.

How are parasites transmitted from animal to animal?

While in the gastrointestinal tract, parasites lay microscopic eggs that shed in the animal’s feces. Once on the ground in the feces, the parasite eggs develop to contain larvae that hatch on the ground. The larvae then develop to the stage where they are capable of infecting another animal. The time needed for this maturation step is variable, but in general it occurs over a matter of several days during warm weather. During very cold weather, maturation can be delayed for weeks to months. The larvae are capable of traveling a small distance (millimeters to centimeters) away from the fecal matter and reside on nearby blades of grass or other plant matter, such as hay that is on the ground. Larvae can be spread by animals walking in their manure and stepping onto nearby grass or feed, which is then ingested by another animal.

Note that contamination of feed by fecal matter is the primary means by which these parasites are introduced into the host – this is a critical point in controlling parasites with good management.

Once ingested by the goat, the parasite matures in the gastrointestinal tract into the adult form, and egg laying resumes. In optimal conditions, this entire cycle can be completed in less than three weeks, so pasture contamination with parasite eggs can become massive in a short period of time. Most damage to the host is caused by either the maturing larvae or the adult forms of the parasites, and in some cases both larvae and adults can contribute to disease.

What are some of the ways that farm management can be changed to limit parasite problems in a goat herd?

1.

Don’t feed hay or grain on the ground. Instead, feed from racks or feeders and keep these clean. The goal is to limit fecal contamination of feed. Goats have a tendency to want to climb into or on top of feeders, so these may need to be covered or modified to prevent them from stepping in or defecating into the feed. Rake up spilled feed and clean water troughs and bowls regularly to limit transmission of parasites through fecal – contaminated water.

2.

Don’t overgraze pastures. If your animals are allowed to graze pasture, move the animals to new pasture (or use an electric fence to section the pasture) every seven to 10 days, particularly during the height of the growing season where warmer temperatures and moisture is maintained. Once a pasture has been grazed, mow it short (2 inches or less) and remove the clipped forage. Exposure to sunlight for three to four weeks will kill many of the remaining parasite larvae, making the pasture safer for goats to return to graze.

Alternatively, you can move horses or poultry onto the pasture – when these other animals ingest parasite larvae from goats, the larvae are not able to mature and will die without causing harm to the “new” animal that ingests them. The goats can be returned to this pasture in about four to six weeks, provided that the alternate animals have disrupted the fecal pellets left by the goats (poultry) or grazed the grass down extensively (horses).

Goats do very well if allowed to “browse” – that is, eat the leaves and stems of shrubs and tall weeds at shoulder height to the goat. The parasites shed in feces will not contaminate the plants at this height off of the ground because the eggs and larvae will be on the ground or on short plants nearer the ground level. Pastures intended for grazing can be cultivated with certain plants that show promise in helping to control parasites in goats. These plants – such as Sericea lespedeza and birdsfoot trefoil – contain compounds called condensed tannins, which appear to suppress egg production by certain gastrointestinal helminths.

3.

Avoid overcrowding – Because most gastrointestinal helminthes are transmitted directly from one host to another, many parasitism problems arise from overstocking, or simply having too many animals on a given section of land. Overcrowding contributes to added stress on the animals as well as added competition among the animals held in small confined areas. This is particularly true when goats are grazing small pastures.

4.

Use deworming medicine (called anthelmintics) wisely. Your veterinarian can test the feces of your goats to determine the level of parasitism present in your animals, and he or she can then custom design a deworming strategy to fit your situation. There is no single schedule for deworming treatments that fits all of the needs of all farms and ranches. To avoid treating your animals when they don’t need it, and to avoid delaying treatment until animal health is compromised, consult with your veterinarian on how best to use these medicines. Haphazard use of deworming medicines can induce anthelmintic (dewormer) resistance of the parasites, and the medicines may permanently lose their efficacy to kill the gastrointestinal parasites found in goat herds. Loss of anthelmintic efficacy becomes especially important if these drugs are over-used.

5.

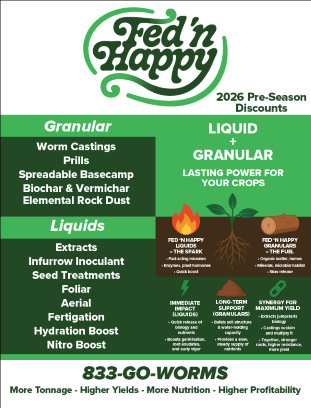

Avoid malnutrition. Goats are far more capable of coping with gastrointestinal parasites if their nutritional needs are met. Feeding adequate amounts of protein to these animals is particularly important. Your veterinarian can help you to design a nutritional program that best fits your animals’ needs. Combining the judicious use of anthelmintics, adequate nutrition, and good flock/herd management will greatly diminish the negative effects of gastrointestinal parasites in your goats.

1. D. Van Metre, DVM, DACVIM, Colorado State University Extension specialist (veterinarian) and associate professor, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Clinical Sciences. (5/2010).

Colorado State University, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Colorado counties cooperating. Extension programs are available to all without discrimination. No endorsement of products mentioned is intended nor is criticism implied of products not mentioned.

September 2024

By D. Van Metre of Colorado State University Extension

For Leading Cattle Industry News: Home – American Cattlemen