Housing for Dairy Calves

Housing for Dairy Calves

Young dairy calves have traditionally been housed in single-calf hutches, because this has generally been believed to be healthier for them than having contact with other baby calves. Recent research and behavioral studies are showing that there are benefits to paired and group housing.

Joe Armstrong DVM (Cattle Production Systems, Extension Educator, University of Minnesota) says there are many different options today. “The biggest thing we are looking at right now is the advantages and disadvantages of individual, paired, or group housing. The goal with individual housing is biosecurity. If that single calf gets sick, it’s less likely that the animals around it will also become sick,” he says.

“Paired housing has some advantages. However, studies have shown potentially better growth with paired calves because of the social interaction between those calves. The issue with paired housing is that it doesn’t necessarily decrease the amount of labor to take care of calves. This is where group housing (usually five or more calves) comes in, as we try to balance it out—with less labor requirements, using our labor in a different way, while still having some social dynamics in a group setting,” says Armstrong.

The math on social dynamics, to work well, is somewhere between five and 10 calves in a group. “Having five to six calves seems to work really well. This may be the optimum number; you don’t want too many. Socially, for whatever reason, dairy calves just don’t do well in really big groups. In a smaller group it’s also easier to keep track of which ones are healthy and which ones are having an issue, and whether each of them is eating.”

Socially, in a large group there are issues with pecking order, and some calves are continually being picked on. “The social dynamics just seem to work better when we have much smaller groups,” he says. The calf still has a buddy or two but there’s not as much competition Cattle can often be very competitive for resources and may prevent resource access to the most subordinate members of the group. Also, if one gets sick, the others may have a tendency to pick on the sick animal.

The social factor is one part of a decision regarding housing, and the other is what kind of building or facility you put the calves in. “This basically comes down to finding ways to minimize heat and cold stress, and also labor considerations. The type of facility you create will depend on your location and climate, in terms of dealing with heat and cold stress. Proper ventilation is a huge factor in all of this.”

Efficiency for labor and comfort for the people taking care of the calves are additional factors to take into consideration. “Efficiency is a big deal, especially when you are short on labor. Having a comfortable environment for the employees to work in is obviously a big piece of the equation, in terms of keeping labor around,” says Armstrong.

Individual housing can include calf hutches, or buildings with individual calf pens. “In the group housing side of it, there are also some different options like super hutches, mono-slope barns, etc. A lot of it comes down to ventilation, climate, and ways to prevent heat and cold stress,” he says.

Feeding methods may vary, in group situations. There are several different systems. Each operation must figure out what works best for their own dairy. “That’s the good thing about the cattle industry and dairying; each operation has a choice, and it’s not cookie cutter or one size fits all. In my mind, that is actually a good thing because it allows people to be flexible and make their own choices,” says Armstrong.

“There is no right way to do it and no wrong way to do it; each operation has to choose what works best for them and then manage the calves as best they can within that framework. We have done several podcasts on calf housing, each about 30 minutes long,” he says. Anyone who wants to get more details can access these podcasts by going to The Moos Room Podcast – z.umn.edu/themoosroom. Episodes 93, 94, and 176 are related to calve housing.

Dr. Bob James, a dairy consultant and owner of Down Home Heifer Solutions, Blacksburg, VA (Former Extension Scientist at Virginia Tech) specializes in calf management and nutrition. He works with many dairies across the country, helping them do a good job with their young stock.

“I also work with a nearby dairy and they have done a great job of demonstrating the many positives with group housing, if a person does the important things the right way.” The calves do better in pairs or groups than in single housing, as long as they have enough to eat and are not hungry and sucking on each other.

This farm has three week-old calves drinking as much as three gallons of milk a day. They don’t all drink that much; some only drink two gallons a day. These calves are all healthy; some just have bigger appetites. “The feeding program that I really like, for the automatic calf feeder, is that we feed each calf individually for a couple of days, just to make sure that everything is fine, and they have a good appetite, and then we put them on the feeder, show them where the nipple is, and let them drink what they want,” he says.

“The old idea that if we feed them that much milk they will not eat calf starter grain is not true,” James says. Beef calves have all the milk they want and need, yet they start nibbling solid feed at a few days of age, mimicking mom, and begin ruminating at an early age. Calves housed in pairs or in a group rather than individual pens also start eating calf starter earlier. They learn from their pen mates. If there is straw bedding in the pen they also start nibbling on it.

“Calves do better with a buddy or peer group. It’s amazing how much calmer they are, and they learn from their buddies,” says James. This is a more natural situation than having calves in individual hutches, since cattle are herd animals.

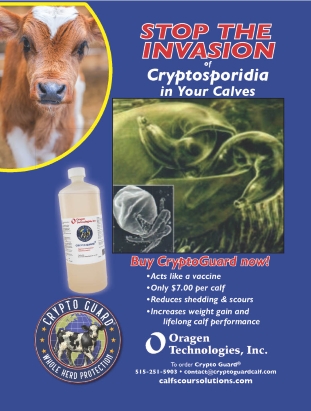

Getting people to feed dairy calves more milk is a challenge. “We are asking these farmers to spend more money. Then we throw in the idea of housing the calves in pairs or groups. This goes counter to our long-standing veterinary recommendations of limiting calf-to-calf contact. Veterinarians have not been very keen on paired or group housing. The risks of calf to calf contact must be managed by making sure the farm has an excellent colostrum program. Also, if calves are in an indoor facility there must be very good ventilation and a high level of sanitation. It’s not something you can cut corners on to save labor, or it will be a disaster,” says James.

How the heifer calves are raised has a big impact in terms of how these animals behave as cows. The paired and group-raised calves, when this is done right, are better adapted to herd life, have better health and longevity, better milk production, etc. so it can be well worth the effort when managed correctly. Another concern for dairy calf management is consumer perceptions. Research has shown that consumers are attuned to how we raise calves.

October 2023

By Heather Smith Thomas

If you would to read another article around calving techniques

F0r Cattle Industry News:

If you are an Outdoor Enthusiast, The Iowa Sportsman is the place for you.