Managing Internal Parasites in Dairy Cattle

Managing Internal Parasites in Dairy Cattle

Internal parasites are a constant but often overlooked challenge in American dairy herds. While many herds focus on mastitis control, reproduction, and nutrition, parasites, like intestinal worms, begin to decrease productivity behind the scenes. Even when infections aren’t obvious, they can reduce milk yield, slow growth in replacements, impair fertility, and increase treatment costs. Economic losses from parasites occur both through visible clinical disease and through subclinical effects that reduce efficiency without causing clear signs. Parasite control starts with understanding the major parasites that affect cattle, recognizing their economic impact, and using the right diagnostic tools to guide control strategies.

Major Internal Parasites of Dairy Cattle

Several groups of internal parasites commonly affect dairy cattle in the United States. These include gastrointestinal nematodes (roundworms), liver flukes, tapeworms, and coccidia. Each group has its own impacts, and control challenges.

Gastrointestinal nematodes such as brown stomach worms, Cooperia spp., and Haemonchus placei are among the most economically important. These parasites live in the stomach or small intestine, where they damage the gut lining and interfere with nutrient absorption. Calves and young stock are particularly vulnerable, but adult cows can also we affected by them too. Heavy infections may cause diarrhea, weight loss, poor body condition, and reduced feed efficiency. In grown cows, effects are often seen as milk production declines gradually, and animals may fail to maintain body condition even on good feed. Nematodes have a direct life cycle: eggs are shed in manure, hatch into larvae on pasture, and are then ingested by grazing cattle. Pasture management plays a major role in controlling these parasites. We need to disrupt the cycle.

Liver flukes are less widespread but can be a serious issue in areas with wet pastures or irrigation. Cattle become infected by ingesting larvae on pasture. Immature flukes migrate through the liver tissue, causing inflammation and scarring, while adults settle in the bile ducts and impair liver function. Chronic fluke infections can lead to reduced milk yield, slower growth, poor fertility, and sometimes bottle jaw (fluid swelling under the jaw) caused by protein loss. Because fluke eggs don’t appear in feces until weeks after infection, early cases are easy to miss.

Tapeworms primarily affect calves and young heifers. They’re transmitted through pasture mites, and while usually less harmful than nematodes or flukes, heavy infections can cause digestive upset and poor weight gain. Tapeworm infections often indicate grazing management issues, as they depend on access to mite-infested pasture. This cycle too needs to be managed and disrupted.

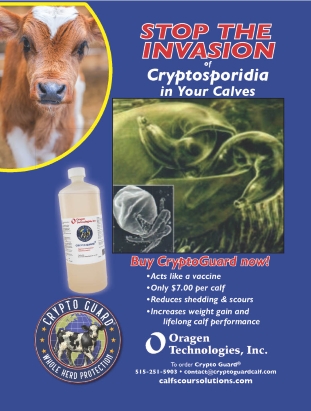

Coccidia mainly affect calves and young stock. Infection occurs when animals ingest oocysts shed in manure. Once inside the intestine, coccidia multiply rapidly and damage the gut lining, leading to diarrhea, dehydration, and reduced growth. Even subclinical infections can slow weight gain and increase susceptibility to other diseases. Stress, overcrowding, and unsanitary calf housing increase the risk of outbreaks.

Economic Impacts

Internal parasites don’t just affect animal health, they affect the bottom line. Economic losses come from reduced milk production, lower growth rates, decreased fertility, carcass condemnation, treatment costs, and labor. Several studies have tried to quantify these losses, and while numbers vary by region and herd, but it is clear that parasites cost dairies real money.

For gastrointestinal nematodes, research has shown infections can reduce milk yield by roughly 1-2 lba per cow per day in affected herds. Over a lactation, this can mean hundreds of pounds of milk lost per cow. If you spread that over your whole herd and over any amount of time, that quickly adds up! A national-level analysis in Mexico estimated losses of $248 million annually from GI nematodes alone, largely through reduced milk production. Farm-level economic modeling consistently shows that strategic deworming and grazing management produce measurable financial returns when milk price and prevalence are factored in.

Liver fluke is also associated with significant losses. A recent study in New Zealand estimated the cost of infection at $ 36–$40 (U.S dollars) per infected cow, mainly from reduced milk yield. Fluke damage to the liver also affects reproduction and can increase susceptibility to other diseases, adding indirect costs. Because fluke thrives in wet environments, the economic impact is highest in regions with irrigated or low-lying pastures.

Coccidiosis causes losses primarily in young stock. Severe outbreaks can cause calf deaths, but even moderate infections delay growth and increase the age at first calving. Economic estimates vary widely, but losses are typically reported in the tens of dollars per calf for subclinical infections. Prevention through good hygiene and early detection is far more cost-effective than dealing with outbreaks after the fact. Still, you want your calves off to a good strong start.

Taken together, these parasites create a hidden but significant drain on dairy profitability. Because subclinical infections don’t cause obvious signs, herds may unknowingly lose thousands of dollars annually unless regular monitoring and targeted control measures are in place.

Diagnostic Tests and Tools

Veterinarians have a range of tools to detect and monitor internal parasites. No single test is perfect, so vets often use a combination depending on the parasite and stage of infection.

Fecal Egg Counts are the most common tool for nematodes. A fresh manure sample is examined under a microscope to count the number of eggs per gram of feces. This gives an estimate of shedding levels and pasture contamination. These tests are inexpensive and useful for herd monitoring, but it may miss early infections or low-level shedders, especially in adult cows.

Larval cultures take fecal egg counts a step further. By incubating samples for several days, eggs hatch and larvae can be identified by species. This allows veterinarians to distinguish between parasites like Ostertagia, Cooperia, or Haemonchus, which is important for choosing the right control strategies.

Bulk tank milk ELISA is widely used in dairy herds to detect antibodies against nematodes like Ostertagia ostertagi. This test measures exposure at the herd level, even when egg shedding is low. It’s especially valuable for adult cows, where FECs are often insensitive.

Individual milk or serum ELISAs can detect exposure in specific animals, providing a more detailed picture. These are often used in young stock or problem cows.

For liver fluke, the sedimentation test is a standard tool. Fluke eggs are heavier than nematode eggs, so fecal samples are washed and examined for eggs in the sediment. This works well for mature infections but won’t detect fluke until several weeks after infection. Coproantigen ELISAs detect fluke antigens in feces and can identify infection earlier than sedimentation, making them useful for early detection and monitoring treatment success. Milk or serum ELISAs can also detect antibodies, giving a broader picture of herd exposure.

For coccidia, fecal flotation is used to detect oocysts in calf manure. High counts, combined with clinical signs like diarrhea and poor growth, confirm the diagnosis. Test results should always be interpreted with age and symptoms in mind. In severe outbreaks, intestinal tissue can be examined post-mortem to confirm damage.

Regular testing provides valuable information for managing parasites effectively. By identifying which parasites are present and when, producers and vets can time treatments more strategically and avoid unnecessary deworming, which also helps slow resistance development.

Practical Control

Controlling internal parasites requires a strategic, integrated approach rather than relying on routine blanket treatments. Here are some key practical points:

The first step is to monitor, don’t guess. Regular testing helps identify problems early and track the effectiveness of control programs. Once identified, target parasites with treatments. Treat animals or groups when diagnostic results or seasonal risk suggest it’s needed, rather than on a fixed calendar. Next, rotate grazing, avoid overstocking, and allow pastures to rest. Breaking the parasite life cycle on pasture is as important as deworming. Pay attention to young stock. Calves and heifers are more vulnerable and often drive parasite transmission on farms. Good hygiene in calf housing helps control coccidia, and strategic grazing reduces nematode exposure.

Additionally, wet conditions or irrigated pastures increase liver fluke risk. Testing and treatment programs should reflect local conditions. Next ask if it is making financial sense. Parasite control has a cost, but the payback in milk yield, growth, and fertility is often significant. Usually it pays off, but look at your particular farm’s finances.

Internal parasites may not always be obvious, but they have a real and measurable impact on dairy herd health and your farm’s bottom line. Gastrointestinal nematodes, liver flukes, tapeworms, and coccidia each pose a threat. Fortunately, testing and diagnostic tools give producers and veterinarians powerful ways to detect and monitor parasite infections. When combined with targeted treatments and good pasture and hygiene management, you can control and disrupt the parasites. American dairymen can reduce hidden losses and improve the productivity and profitability of their operations.

By Jessica Graham

December 2025

More Cattle Industry News found here

If you enjoy the Outdoors stop by the Iowa Sportsman